Mientras las ciudades que dependen de la producción de carbón se enfrentan a la amenaza de la extinción, la comunidad de Collie, en Australia Occidental, ofrece un ejemplo prometedor de cómo sobrevivir —e incluso prosperar— durante la transición global hacia energías con emisiones netas cero.

Una tarde de 1883, el ganadero George Marsh pastoreaba sus ovejas en las colinas verdes y onduladas del Valle del río Collie, en Australia Occidental (AO). Al caer el anochecer en ese terreno salvaje, Marsh recogió unas piedras oscuras junto al río y las colocó alrededor de su fogata. Para su sorpresa, las piedras se prendieron fuego.

Así fueron los humildes orígenes de la industria minera del carbón en Collie. 130 años después, el carbón sigue tan profundamente arraigado en la cultura de Collie, como el yacimiento de carbono fosilizado que yace bajo su suelo.

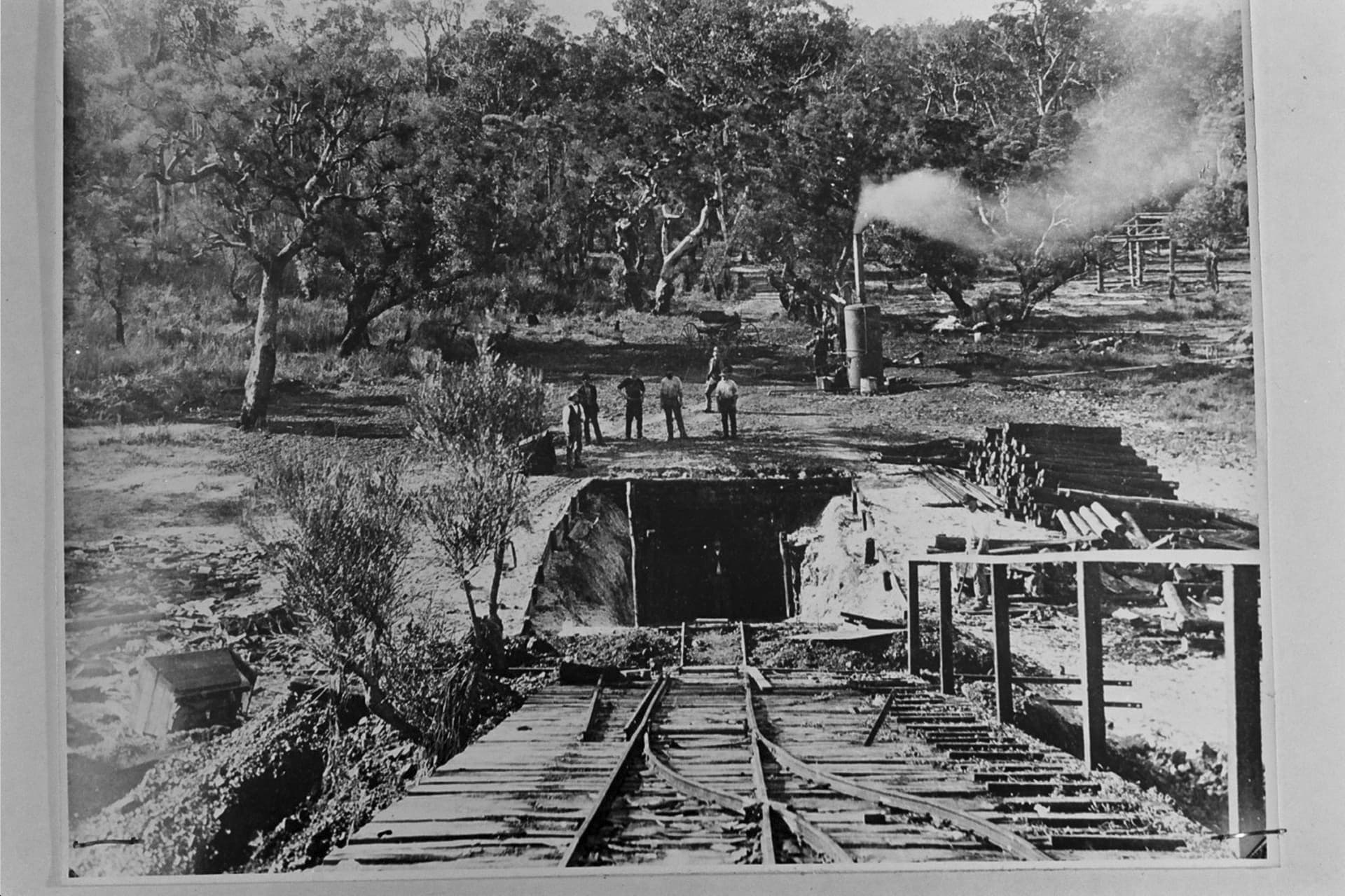

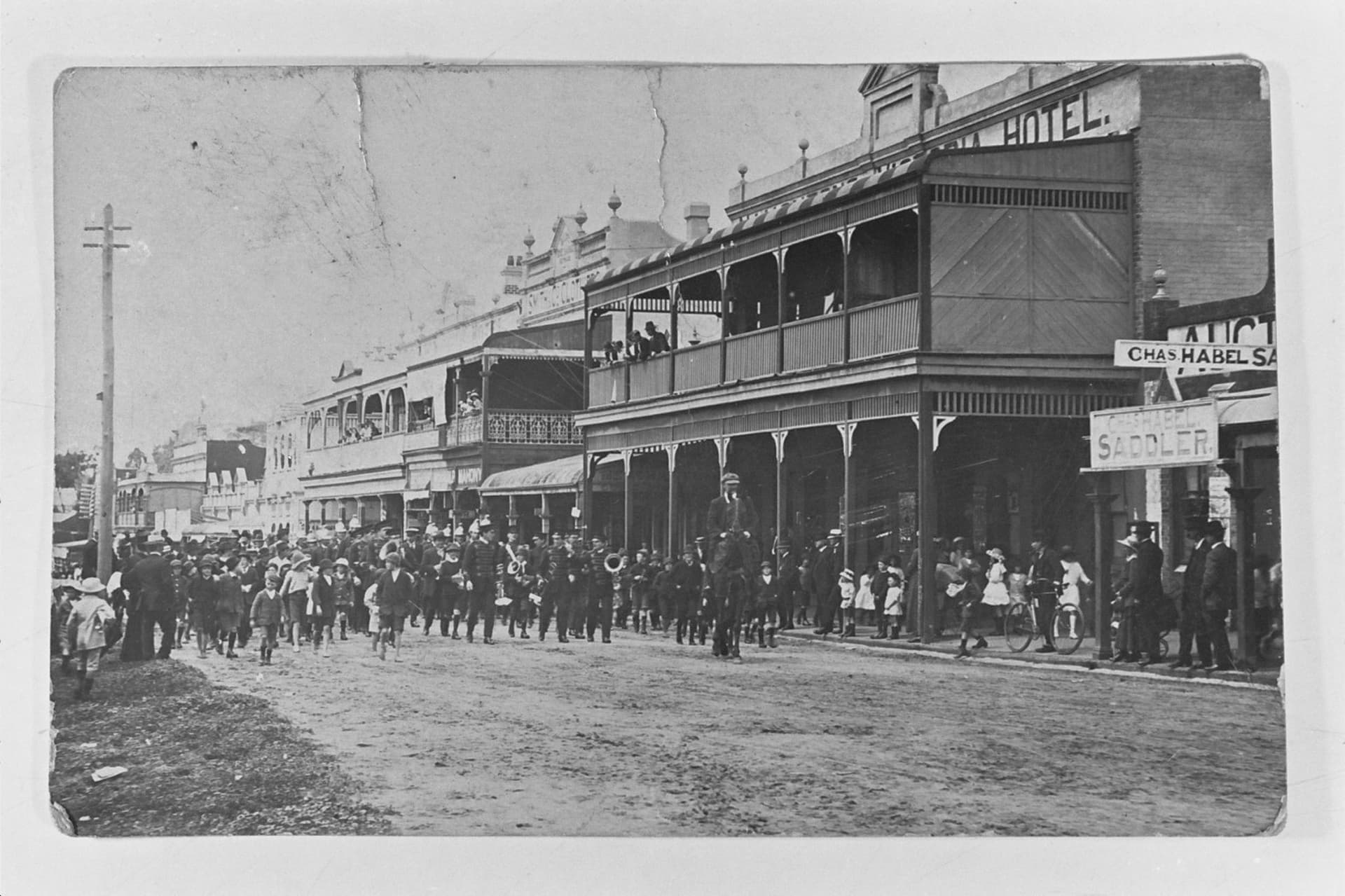

Situada en tierras pertenecientes al pueblo indígena Wiilman Noongar, la zona fue colonizada en la década de 1880 tras el descubrimiento de George Marsh. Pronto se convirtió en el corazón de la minería de en el estado. Sus dos minas de carbón y tres plantas termoeléctricas han abastecido al South West Interconnected System, la red eléctrica principal de Australia Occidental, desde 1931.

El carbón ha sido parte integral de la economía de Collie desde la fundación del pueblo en la década de 1880. (Credit: Griffin Coal)

“Crecí aquí, y recuerdo sentir los temblores cada noche por las explosiones subterráneas”, recuerda Ian Miffling, actual presidente del Shire (alcalde) de Collie. Con el tiempo, Collie dejó atrás la minería subterránea profunda y, en la década de 1990, pasó a utilizar minas a cielo abierto. Hoy en día, visitar las minas a cielo abierto en las afueras del pueblo es como entrar en otro mundo: enormes abismos grises que se extienden hasta donde alcanza la vista, un paisaje antropogénico de proporciones épicas. Al ojo humano le cuesta asimilar la perspectiva: topadoras y camiones de 30 toneladas parecen juguetes sobre un paisaje lunar.

Alrededor de 1,300 personas de los 9,000 habitantes de Collie trabajan en la industria del carbón – una cifra que se acerca a 1,800 si se incluyen los contratistas y trabajadores auxiliares. En el corazón del pueblo, la calle principal está atravesada por una solitaria vía de tren: una arteria vital cuya única función es transportar, sin cesar, el carbón de las minas de Collie a las diversas plantas eléctricas que mantienen encendida a Australia Occidental.

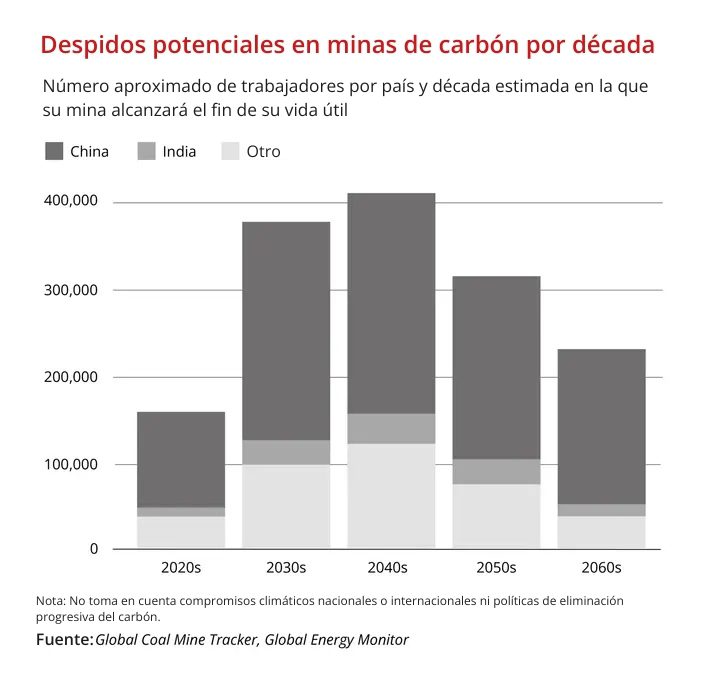

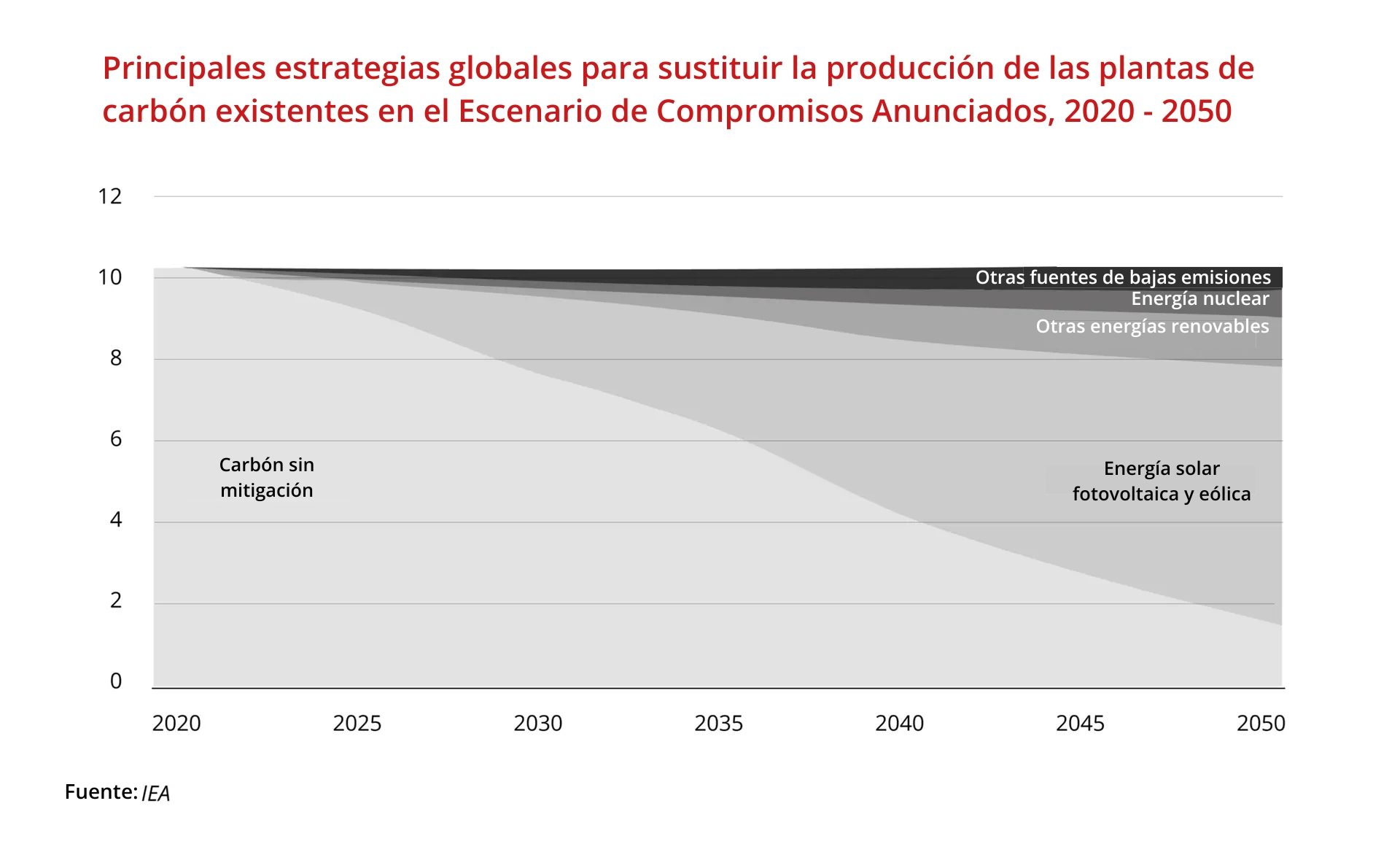

Collie es un microcosmos de la transformación que vive actualmente la industria del carbón a nivel mundial. Mientras las regiones productoras de carbón en el mundo luchan por descarbonizar sus economías de aquí a mediados de siglo sin devastar a las comunidades locales, el pequeño pueblo de Collie ofrece un modelo prometedor para una “transición justa” fuera del carbón, una que respeta plenamente los derechos humanos y laborales de sus trabajadores. Con la transición energética amenazando con eliminar más de un millón de empleos relacionados con el carbón en todo el mundo para 2050, Collie ha logrado atraer cerca de 700 millones de dólares australianos en inversiones para recapacitar y reubicar a su fuerza laboral minera, revitalizar su calle principal y su economía turística, y atraer nuevas industrias verdes como el almacenamiento de energía en baterías, el procesamiento de grafito, el acero verde y el refinamiento de magnesio.

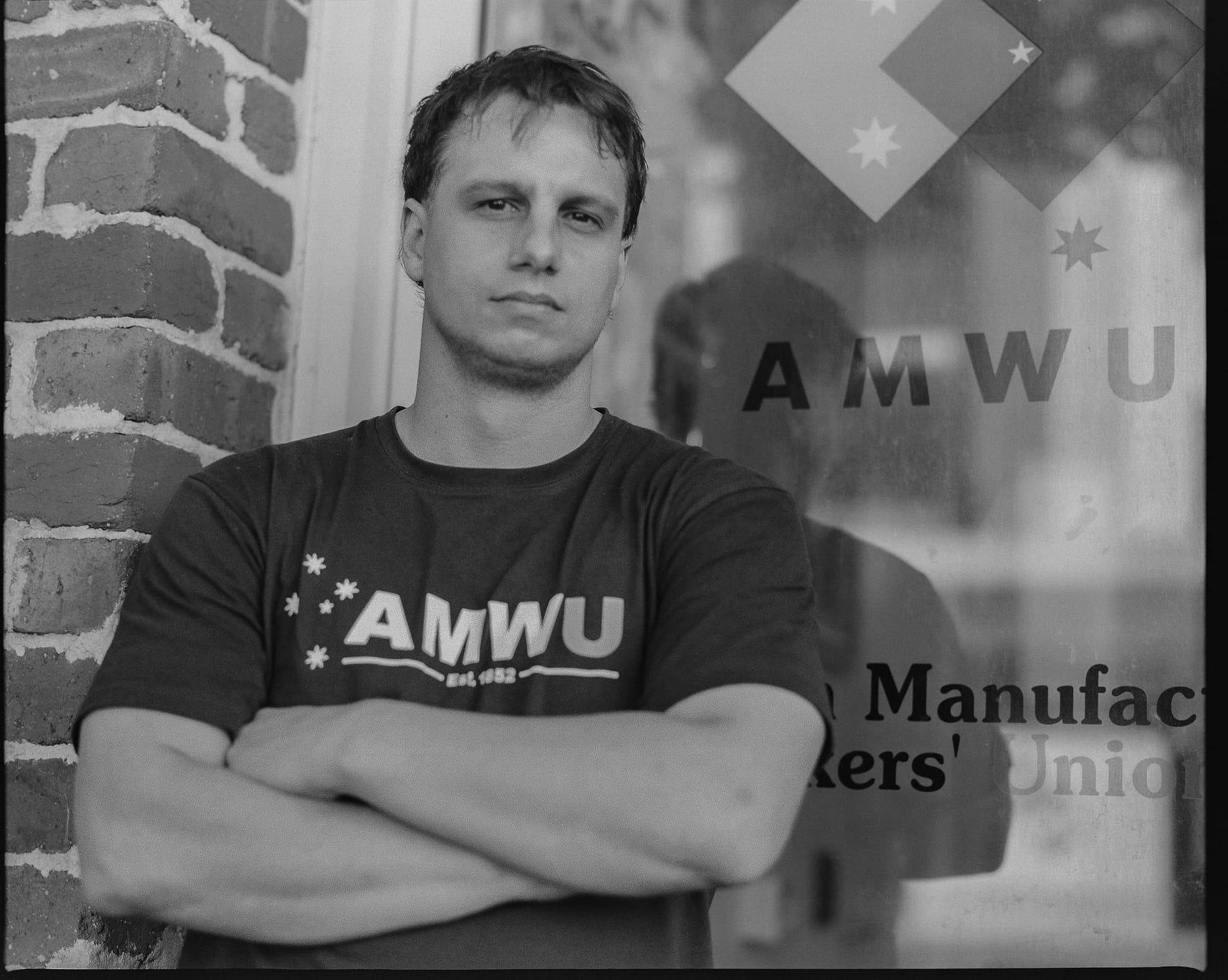

“Llevo el carbón en la sangre”, dice Chad Mitchell, un minero de tercera generación en Griffin Coal, cuya familia ha vivido en Collie durante seis generaciones. A pesar de los desafíos que plantea el incierto futuro de su empleador, sigue siendo optimista. Está por jubilarse anticipadamente, pero le han impresionado las oportunidades de formación que están disponibles para los mineros más jóvenes. “Los sindicatos han intervenido como un soporte, tomando buenas decisiones y ayudándonos a trazar un plan sólido. Los compañeros del trabajo pueden hacer cursos dentro o fuera de su oficio – adquirir conocimiento no representa una carga.”

Ian Miffling, Presidente de Shire, Collie. (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)

Sin embargo, este progreso no fue impuesto desde arriba – es el resultado de una colaboración comunitaria e intersectorial, forjada a lo largo de casi dos décadas de lucha constante. Después de haber abastecido de energía a la región durante más de un siglo, las plantas termoeléctricas públicas de carbón de Collie –Muja y la central de Collie– serán apagadas progresivamente para 2029. El futuro de las minas de carbón del pueblo, Griffin Coal y Premier Coal, así como de la única central eléctrica privada a carbón, Bluewaters, es incierto. Pero con esta “espada de Damocles” (amenaza persistente) colgando sobre el pueblo, el gobierno, los sindicatos, las empresas y –lo más importante– la propia comunidad han estado co-creando un plan de transición que garantice empleos, estabilidad comunitaria y sostenibilidad económica. Y dado que regiones como los Apalaches (EE.UU.) o Shanxi (China) enfrentan desafíos similares, el enfoque integral y centrado en los trabajadores de Collie podría convertirse en un modelo global importante para los pueblos dependientes de carbón que buscan prosperar en un futuro sin con cero emisiones de carbono.

Collie es un ejemplo extraordinario que reúne todos los ingredientes necesarios.

“El mundo no tiene otra opción más que dejar atrás el carbón; pero las comunidades carboneras como Collie deben tener un futuro renovado que garantice a los trabajadores el apoyo, los ingresos y las oportunidades que necesitan para hacer la transición hacia nuevas industrias sostenibles,” afirma Sharan Burrow, asesora especial de la Comisión Global para Transiciones Energéticas Limpias Centradas en las Personas de la Agencia Internacional de Energía y ex Secretaria General de la Confederación Sindical Internacional (CSI).

“Collie es un ejemplo extraordinario que reúne todos los elementos necesarios. Los sindicatos, el gobierno, la comunidad y los empleadores reconocieron que su futuro estaba entrelazado y se tomaron en serio el reto de co-crearlo. Aún no está todo resuelto, pero sin duda va por el camino correcto.”

La línea de tren que recorre el corazón de Collie. (Credit: Bill Code)

El costo de la inacción

El término “transición justa” es un nombre poco preciso. No existe ninguna transición industrial o económica en la historia que haya sido verdaderamente justa; siempre ha habido al menos algunas personas o comunidades que han quedado rezagadas en el proceso. Este es particularmente el caso de pueblos como Collie, cuya existencia entera se debe al manto de carbón que corre bajo sus pies: “no se trata solo de cerrar la industria del carbón, se trata de deshilachar el tejido social de toda una comunidad,” afirma el Dr. Caleb Goods, profesor titular de Gestión y Relaciones Laborales en la Escuela de Negocios de la Universidad de Australia Occidental (UWA, por sus siglas en inglés), y uno de los principales expertos en transiciones laborales y energéticas. No obstante, estas transiciones deben evaluarse en un espectro de justicia, con el objetivo de incluir a la mayor cantidad de personas dentro de lo posible. Es una tarea sísifa, pero es mejor intentarla que no hacer nada. La historia está llena de ejemplos de lo que sucede cuando se ignora esta tarea o se gestiona mal: comunidades en el norte de Inglaterra y en los Apalaches, en Estados Unidos, todavía hoy sienten las devastadoras consecuencias económicas y sociales de la destrucción de sus industrias carboneras en los años 80. Muchos historiadores incluso creen que los movimientos políticos que llevaron al Brexit y al ascenso de Donald Trump tienen algunas de sus raíces en las purgas mal gestionadas de la industria del carbón que hicieron Thatcher y Reagan.

“La justicia no es solo un imperativo moral, es la base del apoyo público a las transiciones energéticas,” afirma el profesor John Wiseman, de Melbourne Climate Futures, coautor del próximo libro “Transiciones Energéticas Regionales en Australia: De lo Imposible a lo Posible.” Sin embargo, alcanzar dicha justicia requiere planificación con visión de largo plazo e inversión en infraestructura, desarrollo de habilidades e impulso a nuevas industrias para las comunidades regionales – cuya ausencia, advierte Wiseman – corre el riesgo de profundizar la desigualdad y socavar la transición más amplia hacia las emisiones netas cero. “Los costos de la inacción superan por mucho las inversiones necesarias,” concluye.

Australia tiene un historial irregular en este tipo de transiciones. “Somos un país lleno de pueblos fantasmas,” señala Alison Reeve, del Instituto Grattan, un centro de investigación en políticas públicas con sede en Canberra. Los cierres de minas impulsados por políticas públicas y no por el agotamiento natural del carbón, presentan desafíos únicos, advierte. Aunque regiones como Hunter Valley cuentan con suficiente diversidad económica para amortiguar el golpe, pueblos dependientes del carbón como Collie o los del centro de Queensland enfrentan un reto mucho más difícil.

Australia es una economía extractiva y posee algunas de las reservas más importantes del mundo de minerales críticos como el litio y el níquel, que serán esenciales para industrias del futuro, como los vehículos eléctricos, las baterías, los paneles solares y las turbinas eólicas. Pero, aclara Reeve, esas reservas no siempre se encuentran en los mismos lugares que el carbón. “Algunos pueblos carboneros simplemente no sobrevivirán a la transición energética,” admite. La madre de Reeve creció en un pueblo minero en el extremo occidental de Queensland, “pero cuando la mina cerró en los años 50, todos se fueron. Hoy, no queda nada más que algunos restos oxidados de maquinaria.”

Gran parte de los problemas del país en este sentido provienen de décadas de disputas políticas internas. “Quince años de políticas climáticas convertidas en una guerra cultural hicieron caer a cinco primeros ministros”, señala Reeve. El actual gobierno laborista ha subido la apuesta, presentando una ambiciosa agenda climática. Sin embargo, el progreso se ha visto obstaculizado por la resistencia a la infraestructura de energía renovable en las regiones rurales. La coalición opositora —compuesta por los Liberales y los Nacionales— ha sido acusada de instrumentalizar este nimbyismo (rechazo local a proyectos de construcción), y de promover soluciones poco viables como un despliegue masivo de energía nuclear. Pero, siendo justos con el país, hay pocos ejemplos en el mundo de transiciones justas que se hayan llevado a cabo con éxito, e incluso líderes en la materia como España y Alemania han enfrentado grandes dificultades.

En Collie, sin embargo, se encuentra una alternativa incipiente al enfoque típico jerárquico de “arriba hacia abajo”, liderado por el Estado; ofreciendo una fórmula prometedora basada en la planificación liderada por la comunidad. “A diferencia de la mayoría de [los esfuerzos de] transiciones energéticas en Australia, donde la retórica sobre la participación rara vez corresponde con la realidad, la fuerza laboral y la comunidad de Collie han estado en el centro de la construcción”, afirma Bradon Ellem, historiador laboral y coautor de la investigación de Goods sobre las transiciones del carbón.

La Mina Premier Coal cerca de Collie. (Credit: Bill Code)

Ira, aceptación, acción

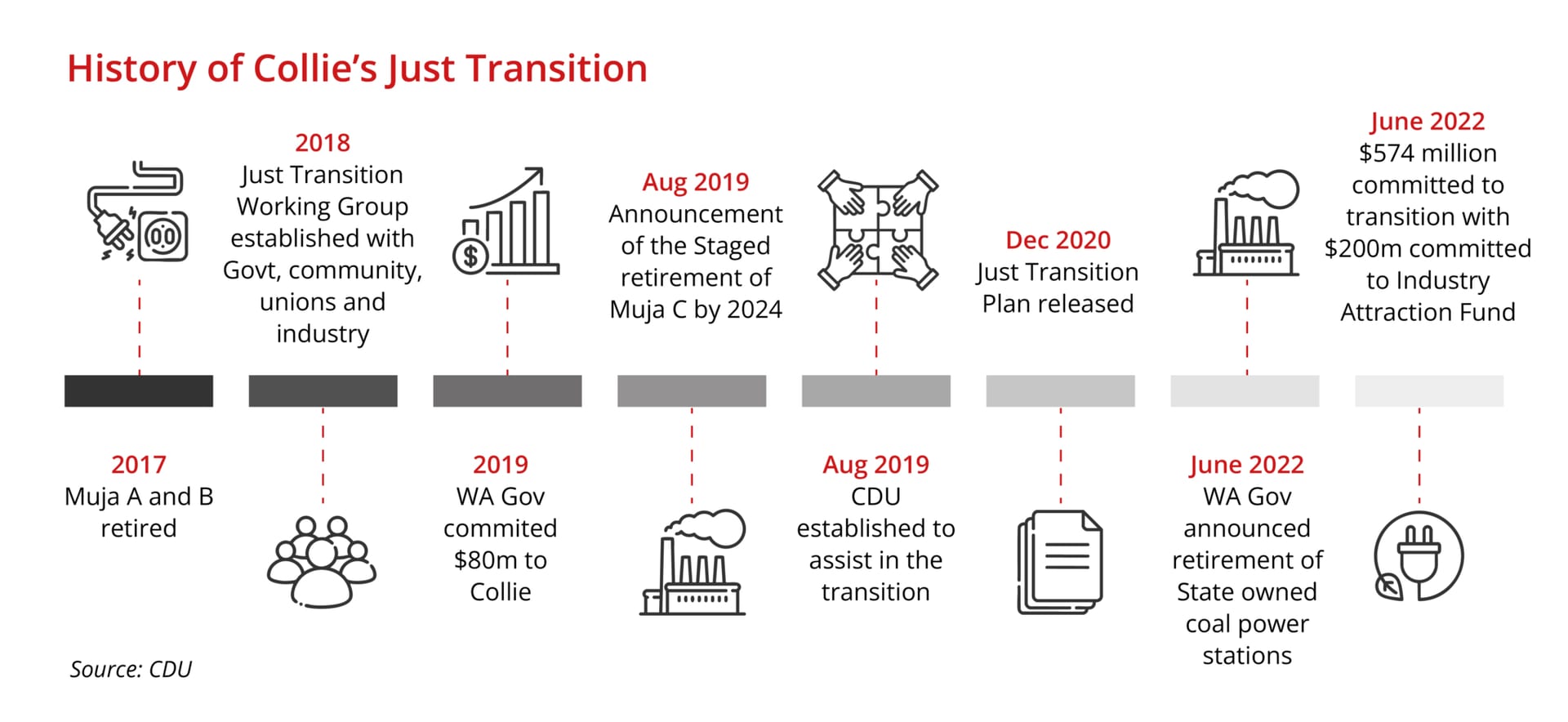

En apariencia, la transición de Collie comenzó en 2017, cuando el Gobierno de Australia Occidental anunció por primera vez planes para cerrar las unidades Muja A y B de Synergy. Para 2022, el gobierno ya se había comprometido a cerrar todas las plantas de energía a carbón de propiedad estatal del pueblo antes de octubre de 2029, incluida la central eléctrica de Collie, que cerraría en 2027.

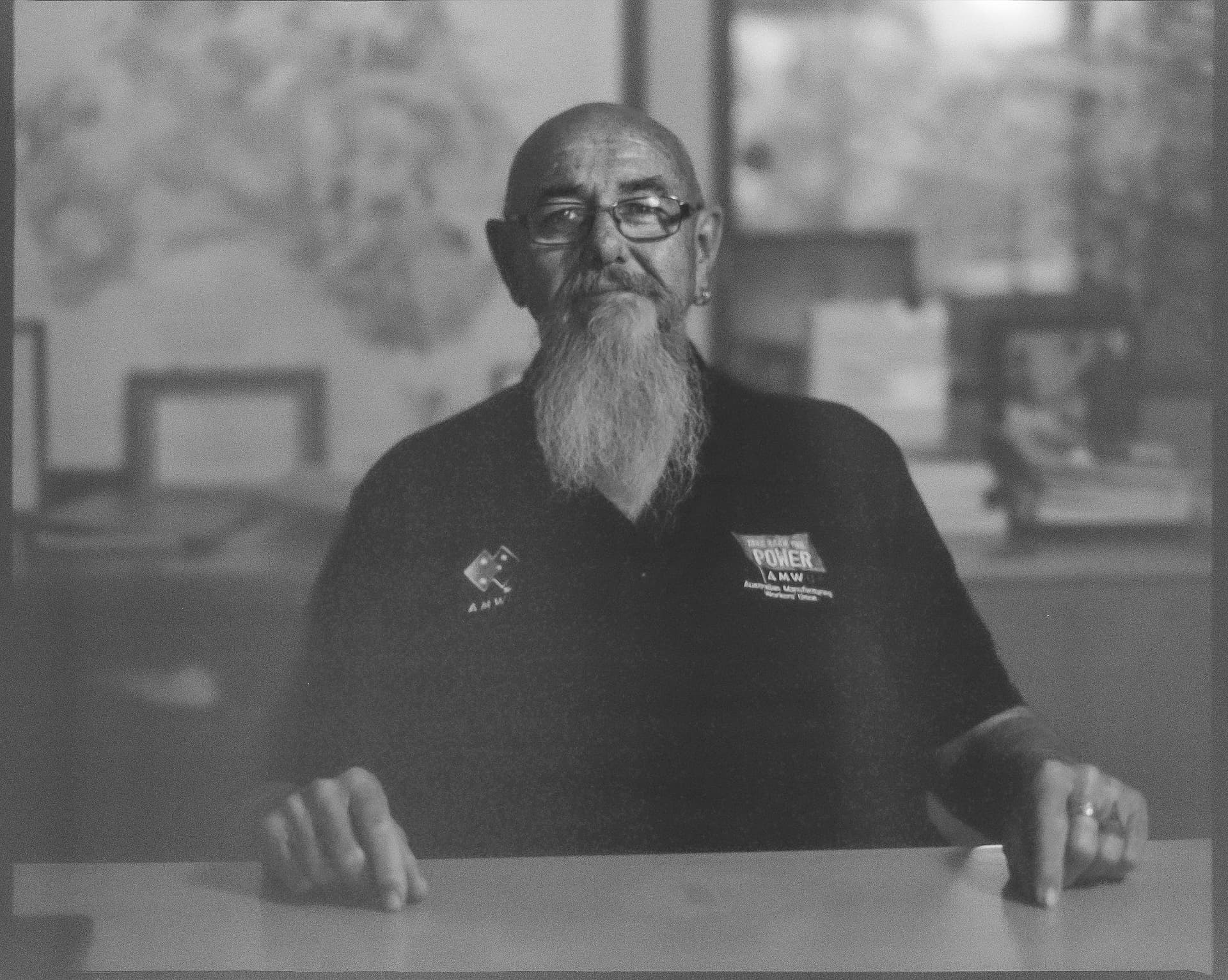

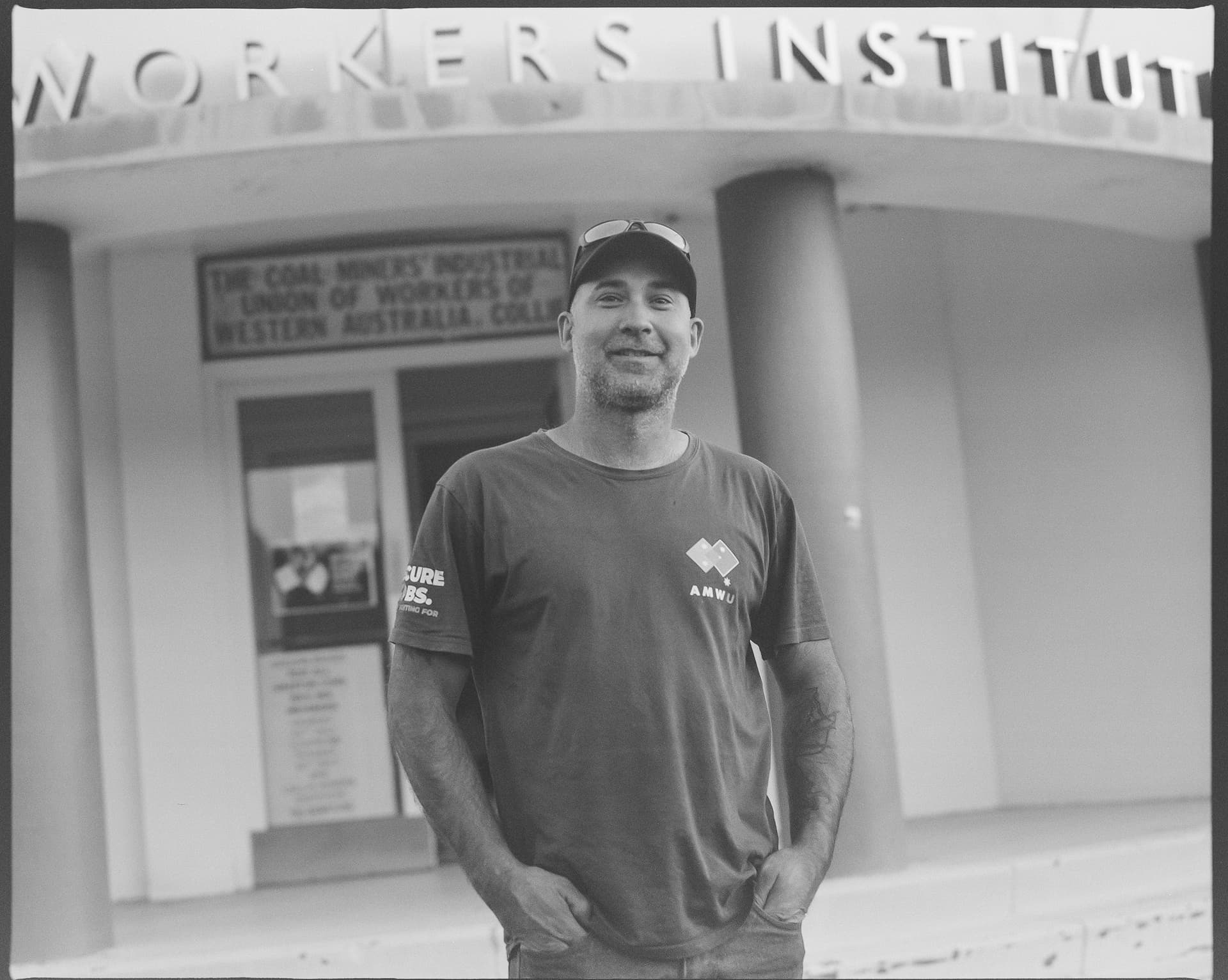

Pero la verdadera historia, en realidad, comenzó una década antes, cuando un veterano sindicalista, con barba de Hells Angel y una inclinación similar por la confrontación, se presentó en una asamblea vecinal con la desagradable noticia de que la industria de carbón de Collie tenía los días contados. “Me dieron con todo”, recuerda Steve McCartney, líder del Sindicato Australiano de Trabajadores de la Manufactura (AMWU, por sus siglas en inglés), cuya actitud directa y propensa a la invectiva oculta un profundo altruismo y preocupación por la gente común. “No les interesaba nada de lo que tenía que decir. Me repetían una y otra vez que en esa colina a las afueras del pueblo quedaban 150 años de carbón.” Rodeado por una multitud enfurecida de 200 trabajadores del carbón, uno de ellos se levantó y le gritó a McCartney: “No tienes idea: cuando nace un bebé en Collie, lo primero que recibe es una teta en la boca y un pedazo de carbón en la mano.”

Steve McCartney, Secretario Estatal de Australia Occidental del Sindicato de Trabajadores de la Manufactura de Australia. (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)

Chad Mitchell, mecánico ajustador en Griffin Coal. (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)

Firme ante la hostilidad, McCartney persistió en sus intentos de convencer al pueblo de transformar su economía. En una reunión a la que asistió en 2018, estalló una “pelea” entre los asistentes. Sin embargo, en la reunión siguiente, McCartney sintió un cambio en el ambiente y las conversaciones comenzaron a volverse más constructivas. Al principio, gran parte de la comunidad estaba en negación, recuerda Miffling. “La gente pensaba: ‘No va a pasar’. Pero, poco a poco, todos se dieron cuenta de que era inevitable.”

En los años siguientes, esas conversaciones evolucionaron hasta convertirse en planes concretos. Cuando el Gobierno llegó a anunciar el cierre progresivo de Muja C en 2019, el pueblo ya estaba preparado; contaban con una estructura sólida y principios firmes para guiar la transición energética. “Queríamos que fuera el pueblo quien decidiera su futuro, no el Gobierno”, explica McCartney. Los habitantes enfatizaron la necesidad de crear empleos sostenibles “que generen otros empleos” y que aprovecharan las habilidades industriales consolidadas del pueblo – empleos que no dejaran a las futuras generaciones en la misma situación con futuro incierto. Querían dejar de ser un “pueblo de un solo empleo”, conscientes de la vulnerabilidad que implica depender exclusivamente del carbón.

Tuve que ponerme de pie frente a mi esposo, amigos y vecinos y decirles que sus trabajos en la central eléctrica de Muja llegaban a su fin. Fue uno de los días más difíciles de mi vida.

Jodie Hanns, miembro de la Asamblea Legislativa de Australia Occidental por Collie-Preston, recuerda la ardua y emotiva tarea de anunciar el calendario de cierres junto al primer ministro estatal, Mark McGowan. “Tuve que ponerme de pie frente a mi esposo, amigos y vecinos, y decirles que sus trabajos en la central eléctrica de Muja llegaban a su fin. Fue uno de los días más difíciles de mi vida.”

La creación del Grupo de Trabajo para la Transición Justa (GTTJ o Just Transition Working Group, por sus siglas en inglés) en 2019 —y su secretaría administrada por el Estado, la Unidad de Ejecución de Collie (UEC)— marcaron un momento clave. El JTWG reunió a todas las partes involucradas en la transición: la comunidad, los empleadores, el gobierno y los sindicatos, todos bajo un mismo techo. “Teníamos a todos en la mesa”, dice McCartney. “Así, las decisiones podían tomarse sin tener que ir y venir hasta Perth,” la capital de Australia Occidental. Subcomités se encargaron de temas específicos, desde la creación de empleo hasta la capacitación, asegurando que cada trabajador contara con un plan personalizado. “Queríamos que la capacitación remunerada ocurriera mientras la gente aún estuviera trabajando, para que no se quedaran atrás”, explica McCartney. “Vimos lo que pasó cuando transicionó la industria automotriz en Australia: si esperas hasta después del cierre para capacitar a los trabajadores, ya es demasiado tarde.”

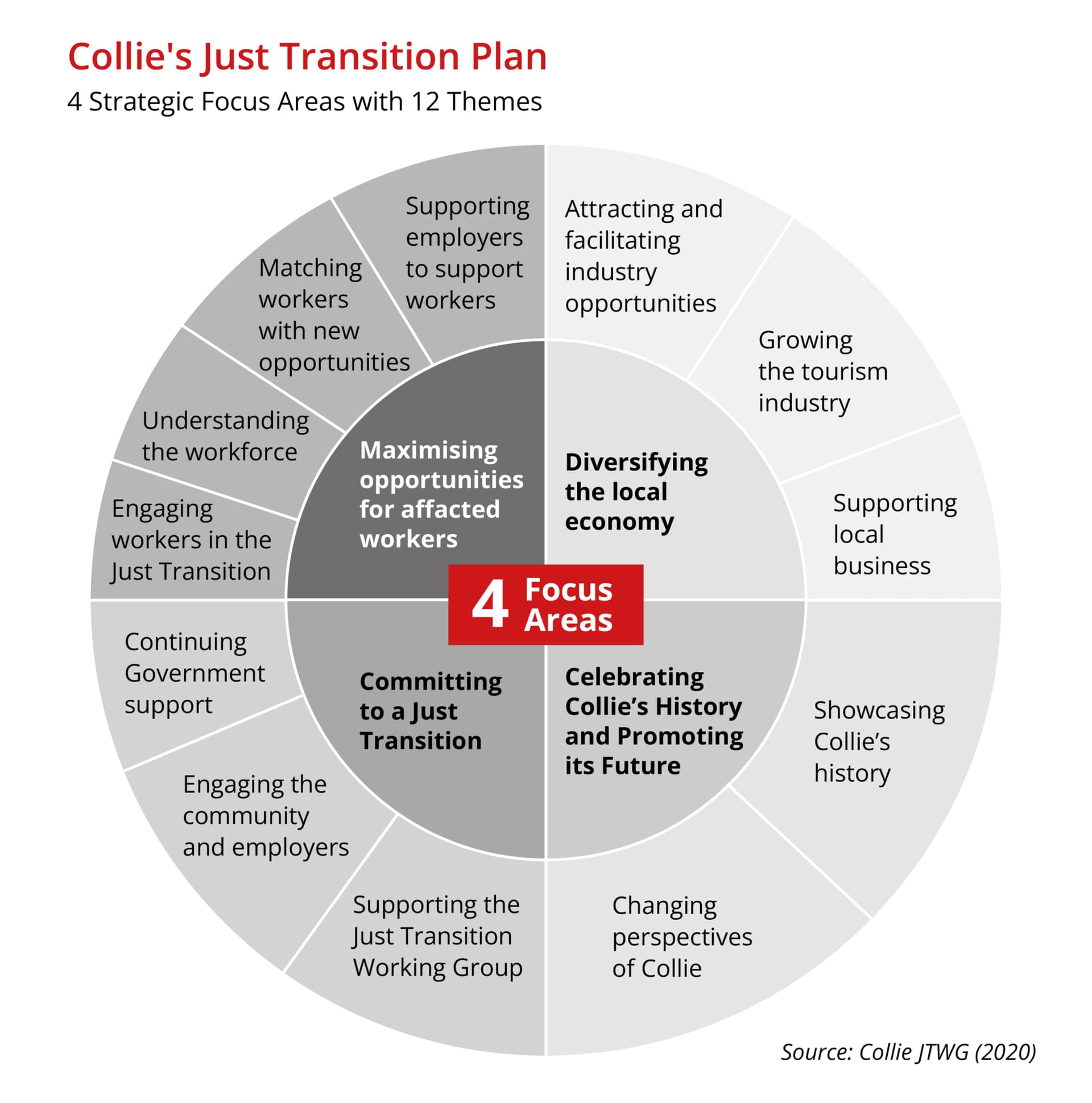

En 2020, el GTTJ y el gobierno estatal publicaron un Plan de Transición Justa para Collie basado en cuatro pilares clave: maximizar las oportunidades para los trabajadores afectados, diversificar la economía local, celebrar la historia de Collie para promover su futuro, y comprometerse con una transición justa según lo definido en el Acuerdo de París de 2015. Para garantizar la rendición de cuentas, la UEC implementó un riguroso registro de acciones con metas medibles y revisiones periódicas.

El enfoque colaborativo detrás de la transición de Collie se basa en la responsabilidad compartida y la acción colectiva. El Gobierno de Australia Occidental lideró el proceso a través del Departamento del Primer Ministro y el Gabinete (DPMG, o Department of Premier and Cabinet, por sus siglas en inglés), el cual, por medio de la Unidad de Ejecución de Collie (UEC), rinde cuentas al Grupo de Trabajo para la Transición Justa (GTTJ), que a su vez vela por que las decisiones consideran tanto a la fuerza laboral afectada como a la comunidad en general. Tener al grupo dentro del DPMG permite superar los esfuerzos aislados entre departamentos, asegurando visibilidad al más alto nivel del gobierno y facilitando la colaboración interinstitucional. Un elemento fundamental de su éxito hasta ahora ha sido el equilibrio entre la experiencia individual de los miembros del JTWG y su compromiso colectivo con la transición.

Cada engranaje está cumpliendo su función: los sindicatos —el Sindicato de Trabajadores de la Manufactura Australiana (STMA), el Sindicato de Servicios Australiano (SSA), el Sindicato de Oficios Eléctricos (SOE) y el Sindicato de Minería y Energía (SME)— desempeñaron un papel esencial al integrar el lenguaje de transición justa en las primeras fases de planificación y al negociar con indicadores centrados en el bienestar de los trabajadores, como: evaluaciones de habilidades, recapacitación remunerada y paquetes de apoyo. El Consejo Municipal garantiza una línea abierta de comunicación con la comunidad. La empresa estatal de servicios públicos Synergy inició un sólido programa de transición laboral, que sirvió de inspiración para los servicios que después ofreció el Centro de Trabajo & Habilidades del Gobierno de Australia Occidental. Además, las empresas mineras privadas, Griffin Coal y Premier Coal, deberán rehabilitar cerca de dos mil hectáreas de terrenos mineros antiguos: una fuente importante de empleo tras el cierre definitivo en 2029, y una oportunidad para reutilizar esas tierras e infraestructuras en favor de las nuevas industrias verdes. Cada actor tiene un papel que desempeñar. Con el tiempo, surgieron tres principios clave que se convirtieron en la base de la transición: crear empleos sostenibles, permitir que los trabajadores se capaciten mientras siguen empleados e inspirar a la juventud a construir el futuro de su pueblo. “Eran principios verdaderamente sólidos”, afirma McCartney.

La transformación

El enfoque de Collie ya ha dado resultados impresionantes. Hasta ahora, el Gobierno de Australia Occidental ha comprometido 662 millones de dólares australianos a la causa, destinados a programas de recapacitación, diversificación industrial y proyectos de infraestructura. Además, el pueblo se beneficiará del programa estatal más amplio de desarrollo de energía renovable, valorado en 3.800 millones de dólares australianos, que incluye un sistema de almacenamiento de energía en baterías (BESS, por sus siglas en inglés) de 1.000 millones que actualmente se está construyendo en Collie.

Las inversiones iniciales en la revitalización del pueblo desempeñaron un papel importante en cambiar mentalidades y generar confianza en la transición energética.

El apoyo financiero para la transición comenzó en 2019, cuando el Gobierno estatal comprometió 115 millones de dólares para iniciativas de apoyo en Collie, incluyendo la creación del Fondo de Atracción y Desarrollo Industrial de Collie, el Programa de Pequeñas Subvenciones de Collie para apoyos comunitarios de hasta 100.000 dólares, y el Fondo para el Desarrollo de Industrias Futuras de Collie, que otorga subvenciones de hasta 2 millones de dólares para que las empresas inviertan en la localidad. Como parte de esto, se han destinado 38 millones de dólares a nuevas iniciativas turísticas, incluyendo inversiones significativas en murales públicos, rutas de aventura, renovación de zonas recreativas y la rehabilitación de la calle principal. Esto ha generado un aumento considerable en el número de visitantes. Hoy, al caminar por la renovada calle principal de Collie, adornada con acogedores cafés, arte urbano, coloridos jardines y hasta una galería de arte, es fácil olvidar que se trata de un pueblo que lucha por su futuro. Más bien se siente como un antiguo pueblo del oeste en plena fiebre del oro —aunque de forma modesta.

Collie ha invertido significativamente en la renovación de su calle principal. (Credit: Oliver Gordon & Bill Code)

“El turismo ha sido un cambio radical”, dice Hanns. La Ruta de Murales de Collie, que cuenta con más de 40 obras de arte público, con el mural más grande del mundo pintado en una represa, y el lago Kepwari —una antigua mina de carbón a cielo abierto transformada en un centro para deportes acuáticos— son solo algunas de las atracciones que están redefiniendo la identidad del pueblo. “Estos proyectos generan empleos de nivel inicial para jóvenes y atraen a nuevos residentes”, señala Hanns. Aunque McCartney era escéptico al principio sobre el impacto de estos proyectos, ahora reconoce que desempeñaron un papel importante en cambiar mentalidades y generar confianza en la transición energética. “Crearon una sensación de cambio, y la gente empezó a entender lo que se podía lograr”.

En 2022, el Gobierno de Australia Occidental anunció que, además de 300 millones de dólares australianos destinados al desmantelamiento de los activos carboníferos estatales de Collie, se asignarían 200 millones de dólares al Fondo de Transición Industrial de Collie para apoyar nuevos proyectos industriales a gran escala en sectores prioritarios como la manufactura verde, el procesamiento de minerales y la energía limpia.

Visitando un nuevo y moderno parque industrial en las afueras del pueblo, el equipo de JUST Stories pasa frente a una instalación de cannabis medicinal, frente a un fabricante de vehículos para servicios de emergencia y una planta de procesamiento de grafito, todos beneficiarios de los incentivos industriales de Collie. Finalmente, aparcamos frente a un enorme cobertizo fluorescente verde, con una audaz promesa estampada: “Reduciendo las emisiones globales en un 1 %”. Se espera que la planta piloto de magnesio verde de Magnium se convierta en una pieza clave de la transición industrial de Collie. Abrió sus puertas en enero de 2025 y aspira a alcanzar la producción a gran escala para 2030.

“Apuntamos a cubrir el 5 % de la demanda global de magnesio”, afirma el director ejecutivo Shilow Shaffier. “La planta a gran escala abarcará 40 hectáreas, generará más de 1.000 empleos en la etapa de construcción y ofrecerá 400 puestos permanentes.” La planta producirá magnesio metálico de bajas emisiones de carbono, un material clave para los vehículos eléctricos y otras tecnologías verdes. “La ubicación, el acceso a la energía y el apoyo de la comunidad hicieron de Collie la elección perfecta”, explica, y añade que los subsidios estatales han sido fundamentales para poner en marcha el proyecto.

De regreso a Collie, pasamos por un terreno industrial lleno de lo que parecen ser contenedores marítimos. Nos informan que se trata del Sistema de Almacenamiento de Energía en Baterías de Collie. Una vez en funcionamiento en 2025, proporcionará 500 megavatios de potencia con 2.000 megavatios-hora de almacenamiento para el Sistema Interconectado del Suroeste, con capacidad para abastecer a 785.000 hogares promedio durante cuatro horas. Operado por la empresa estatal Synergy (que también gestiona las plantas eléctricas estatales de Collie), será uno de los sistemas de baterías más grandes del mundo. “Es una gran oportunidad para los empleados de Synergy”, señala Liz Baggetta, jefa de transición de la empresa. “Algunos ya están involucrados activamente en el proyecto como parte de sus planes individuales de transición laboral.”

El pueblo deposita aún más esperanzas en Green Steel WA, otro pilar clave de la estrategia de diversificación de Collie. La empresa planea construir un horno de arco eléctrico de 450.000 toneladas métricas, alimentado con energía renovable. La planta reciclará acero chatarra para producir productos de bajas emisiones, con el potencial de reducir 800.000 toneladas de CO₂ al año en comparación con la producción tradicional de acero. Nos reunimos con el cofundador Don Johnston en una elegante oficina en un rascacielos del distrito financiero de Perth, una startup rodeada de los imponentes logotipos de gigantes mineros como Rio Tinto y BHP. La empresa espera generar 217 empleos directos en Collie y cientos más en funciones de apoyo. “No estamos construyendo solo una planta; estamos creando un ecosistema a largo plazo que apoye a las familias y fortalezca la resiliencia de la comunidad”, enfatiza Johnston. La empresa se ha asegurado de que los actores comunitarios participen en el diseño del proyecto. “Estamos dando mucho peso a la comunidad en decisiones como la ubicación de la planta, su gestión, las prácticas laborales, los turnos, la forma en que se realiza la recapacitación, etc. Y nos aseguramos de que los inversionistas solo puedan entrar bajo un modelo de ‘lo tomas o lo dejas’, sin renegociaciones con la comunidad”, añade Johnston. Espera tomar la decisión final de inversión a mediados de 2025 y cree que el proyecto se alinea con las capacidades de la fuerza laboral de Collie: “Las habilidades de un operador de carbón se transfieren fácilmente a la operación o mantenimiento de un horno de arco eléctrico”.

La planta piloto de magnesio verde de Magnium abrió en enero de 2025. (Credit: Bill Code)

Terreno minero rehabilitado en la mina de carbón de Ewington. (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)

Una parte importante —y a menudo pasada por alto— de la diversificación industrial de Collie es la rehabilitación de antiguos terrenos mineros destinados a nuevos usos económicos, una obligación establecida en los contratos de concesión minera del Estado. Las dos operadoras de minas de carbón de Collie, Griffin Coal y Premier Coal, han estado trabajando para reconvertir sus antiguos sitios mineros en zonas aptas para el turismo, la agricultura o el uso industrial. En la mina Ewington de Griffin Coal, visitamos un prado sorprendentemente verde que, no hace mucho, era un enorme cráter que parecía llevar al inframundo y que ahora, sirve como un pastoral hogar para 800 ovejas. Premier, por su parte, ha rehabilitado hasta ahora 283 hectáreas con vegetación nativa, de un vasto terreno de 1.731 hectáreas. “Tradicionalmente, rehabilitar una mina significaba restaurar el terreno con vegetación nativa y marcharse”, explica Emily Evans, superintendenta ambiental. “Ahora, nos preguntamos qué industrias podrían operar aquí también.”

En 2022, el Gobierno anunció un paquete de apoyo a la formación que ampliaría el actual Centro de Empleo y Capacitación de Collie para ofrecer una nueva sede ubicada —de manera muy deliberada— en pleno centro de la calle principal, con el fin de brindar asistencia personalizada de carreras profesionales y deformación a los residentes. En su primer año, el Centro ha ayudado a más de 800 personas, elaborando 265 planes de formación e inscribiendo a 172 trabajadores en diferentes cursos. También se asignaron fondos para nuevas instalaciones de capacitación y un fondo curricular dedicado a desarrollar programas de formación en habilidades específicas para satisfacer las necesidades emergentes en Collie. “No podemos capacitar a todos al mismo tiempo —las nuevas industrias aún están evolucionando”, explica Nat Cook, director del JSC. “Así que nos adaptamos a las necesidades cambiantes, ofreciendo desde redacción de currículums hasta asesorías en los propios lugares de trabajo.”

La transición justa debe cambiar la vida de las personas ahora, no en algún momento del futuro; así es como se empieza a establecer la conexión, en la mente de un trabajador, entre la acción climática y una mejora tangible en el bienestar de su vida.

Por otro lado, Synergy —la empresa que opera las centrales eléctricas de carbón— puso en marcha su Programa de Transición Laboral para ofrecer rutas individualizadas a los trabajadores afectados por el cierre de las centrales de Muja y Collie. El programa brinda opciones como recapacitación, reubicación, despido voluntario o jubilación. “Cuando se anunciaron los cierres, pasamos seis meses escuchando a los trabajadores para entender sus preocupaciones y metas”, explica Baggetta, responsable del programa. A partir de esas conversaciones, Synergy desarrolló planes personalizados para ayudar a los empleados a trazar su futuro. Por ejemplo, Khloe, una joven administradora, hizo la transición al área eléctrica con el apoyo del programa. “Financiamos su formación previa al aprendizaje, y ahora está en su cuarto año como aprendiz de electricista; se titulará en 2025”, comparte Baggetta.

La pieza final del rompecabezas de la transición de Collie es su programa de recapacitación. En 2023, el Gobierno destinó 16,9 millones de dólares para crear el Centro de Empleo y Capacitación de Collie (CECC), una instalación ubicada —de manera muy deliberada— en pleno centro de la calle principal para ofrecer asistencia personalizada en orientación profesional y formación a los residentes. En su primer año, el centro ha ayudado a más de 800 personas, desarrollando 265 planes de formación e inscribiendo a 172 trabajadores en cursos. “No podemos capacitar a todos al mismo tiempo —las nuevas industrias aún están evolucionando”, explica Nat Cook, director del CECC. “Así que nos adaptamos a las necesidades cambiantes, ofreciendo desde redacción de currículums hasta asesorías directamente en los lugares de trabajo.” El enfoque holístico del centro también incluye visitas a los sitios laborales, asegurando que los trabajadores puedan acceder al apoyo mientras siguen empleados.

Nat Cook, gerente del Centro de Empleo y Capacitación de Collie (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)

Y aunque la transición de Collie aún está en sus primeras etapas, estos esfuerzos ya comienzan a dar frutos. Los trabajadores de mantenimiento de Griffin Coal han recibido un aumento salarial del 43 %, capacitación pagada, un incremento del 25 % en sus indemnizaciones por despido, un bono de retención de 30.000 dólares australianos y la creación de consejos laborales remunerados como resultado directo del proceso de transición justa. De forma similar, los trabajadores de Synergy acordaron aumentos salariales equivalentes a la inflación más un 1,5 % garantizado hasta 2029, capacitación durante el horario laboral y una extensión de tres meses en sus indemnizaciones.

“Sin estos logros en el camino, ningún trabajador confiaría en mí cuando me paro en una sala y digo ‘entusiasmémonos con el acero verde’”, afirma Darcy Gunning, organizador de campañas del Sindicato de Trabajadores de la Manufactura Australiana. “La transición justa debe cambiar la vida de las personas ahora, no en algún momento del futuro; así es como se empieza a establecer la conexión, en la mente de un trabajador, entre la acción climática y una mejora tangible en el bienestar de su vida. Crear impulso y confianza no se trata solo de tener un grupo de trabajo tripartito, se trata de cumplir desde ahora y vincular ese cambio material con la idea de lo que viene.”

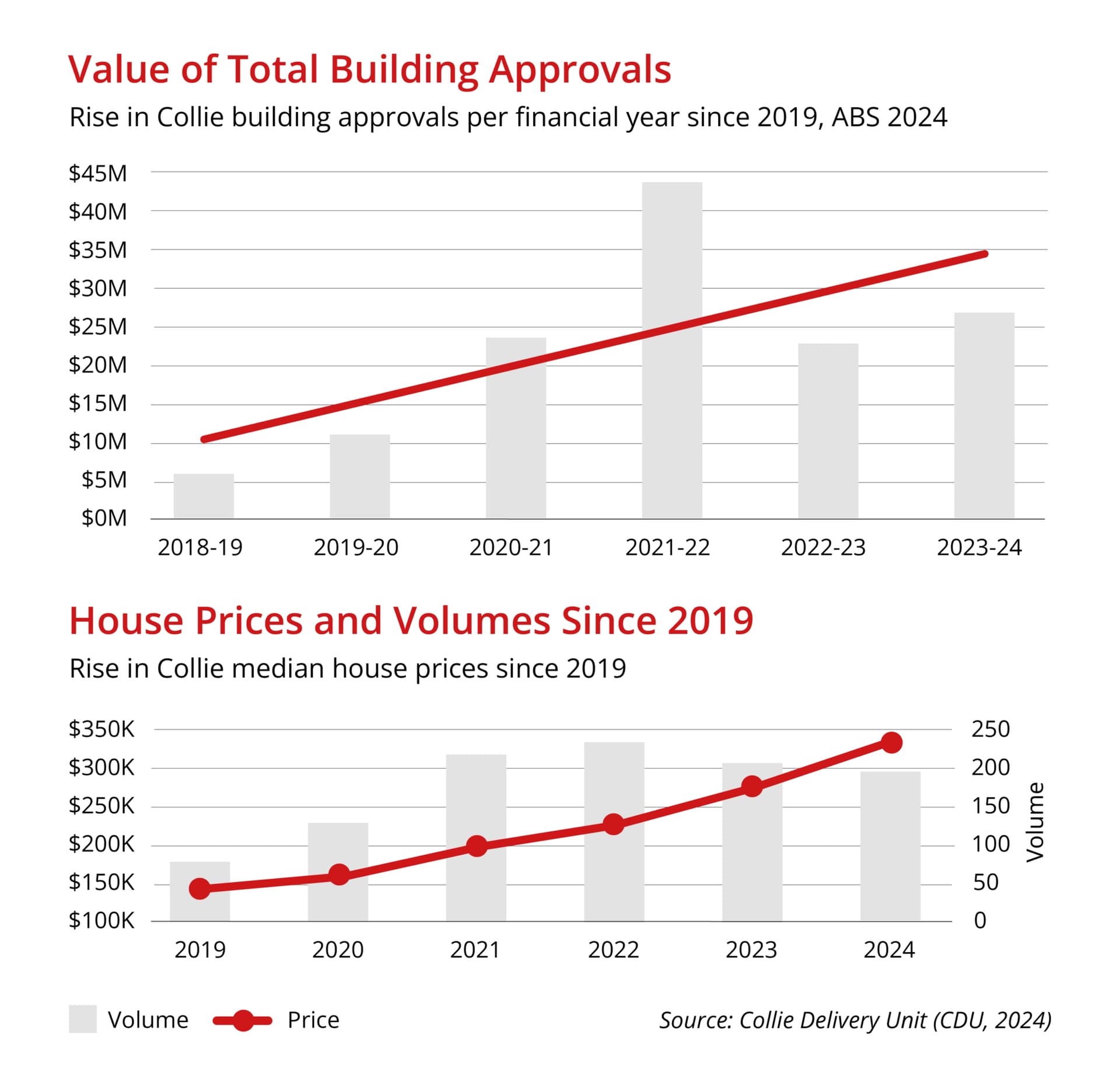

Los éxitos de la transición también están permeando la economía más amplia del pueblo. Desde 2019, la fuerza laboral de Collie ha crecido un 5,4 %, su población un 4 % y las aprobaciones de construcción se han quintuplicado: de un valor de 5,6 millones de dólares en 2018/19 a 26,8 millones en 2023/24. El precio medio de la vivienda ha aumentado un 21 % en el último año, mientras que el número de visitantes anuales también ha crecido. De hecho, Collie quizá se ha convertido en víctima de su propio éxito: algunos residentes mayores que conocimos en la calle principal se quejaban del efecto de gentrificación provocado por jubilados de Perth que se están mudando a Collie en busca de una mejor calidad de vida.

Voces de la transición

Phil Massara, soldador de clase especial en la central eléctrica de Muja. (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)

Para los trabajadores y las familias de Collie, la transición lejos del carbón es mucho más que un simple cambio de trabajo o una modificación de política pública. En muchos casos, implica desarraigar por completo una cultura socioeconómica e identidades que se han transmitido por generaciones. Sus historias personales revelan un abanico complejo —y a veces contradictorio— de emociones y sentimientos: aprensión, optimismo, determinación, mientras enfrentan un futuro incierto.

Pete Wilson es andamiero en la central eléctrica de Muja y se mudó a Collie hace 12 años con su esposa e hijos. “Mi mayor preocupación es tener trabajo”, dice. Reflejando un temor común entre la fuerza laboral de Collie, Wilson espera que los nuevos empleos estén disponibles localmente y no tenga que recurrir a trabajos que “vienen y que van,” o que sólo se encuentran en zonas remotas como Pilbara. “Si todo sale como lo hemos planeado, debería ser algo bueno”, comenta, con cauteloso optimismo.

Para algunos, la transición ha sido una oportunidad de crecimiento personal. Phil Massara ha trabajado en Muja durante 18 años y al principio se sentía aprensivo frente a los planes de cierre. “Al principio, daba miedo”, admite. Pero motivado por el deseo de mantener a sus dos hijas, decidió volver a estudiar. “Soy soldador de clase especial, y estoy cursando el Certificado 10 en supervisión e inspección de soldadura. Es difícil volver a la escuela después de 37 años, pero vale la pena tener algo en qué apoyarse.”

De manera similar, el compañero de Wilson en Muja, Randy Irving, poco a poco empieza a ver los aspectos positivos de la transición. “Soy un hombre de rutinas, así que el anuncio fue aterrador”, confiesa. Pero la oportunidad de recapacitarse y comenzar su propio negocio de chatarra le ha dado motivos para creer que su futuro podría ser incluso mejor que su pasado. “Para alguien como yo, sin mucha educación formal, esta es una oportunidad para aprender algo nuevo. Mucha gente en Collie está en la misma situación.”

La posibilidad de cambio ha sido especialmente difícil para las familias mineras multigeneracionales de Collie. Sean “Kero” Rinder, mecánico de maquinaria pesada en Premier Coal, ha trabajado en la industria durante casi 40 años. “He estado a punto de ser despedido cinco veces mientras las minas se cerraban y reabrían”, cuenta. A sus 56 años, planea jubilarse cuando Premier Coal cierre, pero le preocupa el futuro de sus dos hijos, que trabajan con él. “Ambos tienen por delante carreras de 30 años, y uno de ellos realmente no quiere dejar el pueblo. Los dos están preocupados por lo que viene.” Aprovechar la oportunidad de mejorar sus habilidades será esencial, dice Kero. “Las habilidades básicas se pueden transferir, pero adaptarse a nuevas industrias requiere más que solo experiencia.”

Sean “Kero” Rinder, mecánico de maquinaria pesada en Premier Coal. (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)

Randy Irving, asistente técnico en la central eléctrica de Muja. (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)

Estas preocupaciones no se limitan a los trabajadores de Collie, también son compartidas por otros miembros de la comunidad. Gemma Miles, madre de dos hijos, cree en el potencial de la transición, pero lamenta la falta de comunicación en el proceso. “Es bastante confuso”, comenta. No obstante, ha notado mejoras tangibles en el pueblo. “Los nuevos senderos para bicicletas y los murales… esas cosas marcan la diferencia”, dice. Su esposo llevó a la familia recientemente a uno de los nuevos senderos en bici. “Y yo pensé: ¡guau, esto es increíble!” Está convencida de que el turismo y las nuevas industrias pueden traer empleos sostenibles, pero enfatiza la necesidad de una planificación inclusiva y un mejor acceso a la información. “El otro día hubo una reunión sobre las baterías, pero fue a las 6:30 de la tarde, ninguno de los padres pudo asistir.”

Gemma Miles, residente de Collie. (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)

De manera similar, para la residente Leonie Burton, una transición justa en Collie significa involucrar a toda la comunidad, no solo a los trabajadores. Ella enfatiza la necesidad de una transición comunitaria integral, que sea más respetuosa con los derechos humanos de la comunidad indígena y de otros grupos marginados. Si bien reconoce los avances, también admite que aún hay desafíos por delante. “En el pasado, las discusiones en Perth no incluían a Collie. El gobierno estatal lo está haciendo mejor ahora, pero necesitamos más perspectivas de quienes normalmente no tienen voz, como los Pueblos Originarios y personas con otras experiencias de vida, como personas sin hogar o con problemas de salud mental.”

Leonie Burton, residente de Collie. (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)

Puntos ciegos y desafíos

La transición justa de Collie, como la mayoría de las transcisiones en marcha en el mundo, inevitablemente presenta puntos ciegos e incertidumbres. De cara al futuro, enfrenta una serie de desafíos que podrían hacerla descarrilar antes de alcanzarla meta.

El principal desafío es encontrar reemplazos para la enorme cantidad de empleos que se perderán relacionados con el carbón. Una preocupación común entre los responsables de políticas para avanzar la transición energética es que las nuevas industrias verdes suelen necesitar menos mano de obra que las industrias basadas en combustibles fósiles. A menudo, no están ubicadas en las mismas zonas y los salarios suelen ser considerablemente bajos. Al menos a corto plazo, los trabajos prometidos por nuevos empleadores en industrias verdes emergentes como International Graphite, Magnium y Green Steel WA apenas llegarán a las cientos de ofertas —muy por debajo de los 1.800 empleos relacionados con el carbón que, según estima el Sindicato de Trabajadores de la Manufactura Australiana, necesitan ser reemplazados en Collie. Y eso en el mejor de los casos: muchos de esos proyectos aún se encuentran en etapas iniciales de estudios de viabilidad y están a la espera de financiamiento externo. “Los resultados aún son inciertos. Sin múltiples proyectos a gran escala, todo podría venirse abajo”, advierte Goods, de la Universidad de Australia Occidental, señalando el riesgo de hacer promesas excesivas.

Todo esto es una bomba de tiempo. En cuanto cae una ficha de dominó, hay que correr para mantener las demás en pie.

A esa incertidumbre se suma el calendario de los cierres de empresas privadas. En Collie, las minas y las centrales eléctricas dependen comercialmente unas de otras: Premier Coal abastece a las plantas de Muja y Collie, mientras que Griffin Coal suministra a la central de Bluewaters. Se espera que Premier Coal cierre cuando se apague la última unidad de Muja, en octubre de 2029. Pero el futuro de Griffin Coal y Bluewaters sigue siendo una incógnita. Griffin entró en administración en 2022 y actualmente se mantiene a flote gracias a un acuerdo de financiamiento público, que finalizará en 2026. Si no se renueva —lo cual parece probable— eso también significaría el fin de Bluewaters. “Todo esto es una bomba de tiempo”, afirma Gunning. “En cuanto cae una ficha de dominó, hay que correr para mantener las demás en pie.”

Las próximas elecciones también pesan mucho sobre el futuro del pueblo. Un cambio de gobierno amenaza con deshacer los meticulosos planes de transición justa del actual gobierno laborista. Además de apelar al nimbyismo, la coalición opositora ha propuesto redirigir la transición energética del país de energías renovables a energía nuclear. Esto incluiría extender la vida útil de las centrales de carbón y construir siete plantas nucleares en todo el país entre 2035 y 2050, incluida una en el sitio de la central de Muja, en Collie. Planes que socavarían directamente los esfuerzos del pueblo por alejarse del carbón. Justo antes de nuestra llegada a Collie, los líderes de los partidos Laborista y de la Coalición habían visitado el pueblo con campañas para convencer a la gente de sus respectivas visiones —aunque no conocimos a nadie que apoyara la energía nuclear; lo que sí vimos fueron varias calcomanías de peces con tres ojos pegadas por el pueblo.

La transición de Collie ha sido criticada por algunos sectores de la comunidad por su aparente falta de inclusión, y por no atender adecuadamente los derechos humanos y laborales de los residentes más allá de la fuerza laboral.

Factores culturales y sociales añaden otra capa de complejidad. Para muchos trabajadores de Collie, la minería constituye una parte vital de su identidad; una herencia transmitida de generación en generación. Por este motivo, algunos trabajadores más jóvenes han mostrado resistencia a capacitarse para nuevas industrias verdes. McCartney recuerda que un joven minero le dijo: “Mi abuelo fue el mejor operador de bulldozer en Collie, y mi padre fue el mejor operador de niveladora. A las chicas les gustan los que manejan bulldozers y niveladoras; no les gustan los que usan bata de laboratorio.”

Del mismo modo, muchos de los trabajadores del carbón de mayor edad carecen de educación formal y de habilidades básicas de lectura y escritura, lo que hace que capacitarlos para los nuevos empleos especializados en manufactura sea un desafío intimidante. En una reunión del pueblo, un trabajador confesó: “Dejé la escuela a los 13 y nunca me entrené; no sé cómo hacerlo.”

Según McCartney, alrededor del 10 % de la fuerza laboral sigue “molesta con la transición”, convencida de que la industria del carbón aún puede continuar. De hecho, un minero que conocimos en la mina Ewington creía que la central eléctrica de Bluewaters tendría que seguir funcionando para abastecer de energía a la nueva planta de Green Steel WA, debido a la insuficiente oferta de energía renovable.

Phil Ugle, anciano Wiilman Noongar de Collie. (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)

Stevie Anderson, residente aborigen de Collie. (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)

Dra. Naomi Godden, del Centro para las Personas, los Lugares y el Planeta de la Universidad Edith Cowan. (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)

Como Burton mencionó anteriormente, la transición de Collie ha sido objeto de críticas en ciertos sectores de la comunidad por su aparente falta de inclusión y por no atender adecuadamente los derechos humanos y laborales de los residentes más allá de la fuerza laboral. Una encuesta reciente a 200 residentes, seleccionados por la Climate Justice Union —una coalición de actores comunitarios— reveló que menos de la mitad siente que tiene voz en el Plan de Transición Justa de Collie, y solo el 35 % considera que el proceso es justo. Las voces aborígenes, en particular, han sido marginadas, y los Pueblos Originarios Wilman han sido excluidos de gran parte de la planificación. Phil Ugle, anciano Wilman, expresó su frustración: “No ha habido claridad alguna sobre el proceso de transición. Es imposible conseguir información al respecto. La industria minera destruyó el paisaje aquí, y ahora esta transición corre el riesgo de repetir ese mismo ciclo de exclusión.”

Para Stevie Anderson, otra residente aborigen, la transición debe ir más allá de la industria. “Collie no siempre fue un pueblo minero”, afirma. “Los ancianos deberían estar en el centro del proceso para que puedan mostrar a todos, cómo cuidar mejor del territorio y del río.” Sin una mayor inclusión, la transición corre el riesgo de perpetuar injusticias históricas y de no atender las necesidades más amplias de la comunidad.

Sin embargo, existen soluciones potenciales a estos problemas. A través de un proceso de investigación participativo facilitado por la Unión de Justicia Climática y el Centro para las Personas, los Lugares y el Planeta de la Universidad Edith Cowan (ECU, por sus siglas en inglés), miembros de la comunidad han pedido que los programas de formación y educación de Collie se amplíen para incluir hospitalidad, enfermería, cuidado de personas mayores y estudios ambientales, con el fin de atender a comunidades marginadas. Además, proponen la creación de un programa de “Guardabosques Culturales” para emplear a los Pueblos Originarios Wilman en el cuidado del territorio de formas culturalmente pertinentes. Los ancianos Wilman poseen un conocimiento único del territorio y sus ecosistemas, moldeado por más de 65.000 años de cuidado. “¿Quién mejor que nosotros? Ya gestionamos una transición climática antes. Fue hace 10.000 años y se llamó la Edad de Hielo”, bromea el simpático Ugle con su característica franqueza.

Como explica la Dra. Naomi Godden, del Centro para las Personas, los Lugares y el Planeta de la ECU: “El profundo conocimiento de los ancianos y su comprensión basada en el territorio pueden guiar la transición de Collie, abordando injusticias actuales e históricas para crear un futuro más equitativo.” De manera similar, establecer una línea de subvenciones separada para negocios de propiedad aborigen podría funcionar como una forma de justicia restaurativa.

La Unión de Justicia Climática también busca que la transición atienda las necesidades de otras comunidades marginadas. Abordar la crisis de vivienda asequible del pueblo mediante la construcción de viviendas públicas resilientes al cambio climático no solo proporcionaría hogares de calidad, sino que también, generaría una industria de la construcción que podría sostenerse durante una década. De manera similar, invertir en infraestructura de cuidado infantil permitiría que más mujeres participen en la fuerza laboral. “El cuidado infantil es esencial”, señala Godden. “Crea oportunidades para que las mujeres trabajen, estudien o se incorporen a nuevas industrias, al tiempo que mejora la educación en la primera infancia en el pueblo.” La economía del cuidado representa otra oportunidad aún no explotada: expandir los servicios de salud mental, discapacidad y atención a personas mayores podría generar empleos estables, diversificar la economía y atender necesidades sociales urgentes. Finalmente, como un alivio para las dificultades de los trabajadores, el desmantelamiento de las minas de carbón y plantas eléctricas de Collie ofrece una oportunidad para construir un puente hacia las nuevas industrias. “Tenemos de ocho a diez años solo para limpiar la mina”, dice McCartney. “Eso les da a los trabajadores una oportunidad de desarrollar habilidades transferibles para otras industrias, como la minería de litio, sin tener que abandonar la región.” Los sindicatos también están luchando para que los trabajadores auxiliares del carbón en Collie —como aquellos involucrados en las rotaciones periódicas de cierre— sean reconocidos formalmente dentro del proceso de transición, y así puedan acceder a las mismas oportunidades y beneficios que el resto de los trabajadores del carbón.

¿Un modelo global para la transición fuera del carbón?

El impulso global hacia las energías con emisiones netas cero está acelerando el declive del consumo del carbón, lo cual es una buena noticia para el clima, pero representa un posible desastre para comunidades dependientes del carbón, como Collie. El carbón aún proporciona el 36 % de la electricidad mundial y sostiene los medios de vida de 8,4 millones de trabajadores en todo el mundo. Muchas regiones en el mundo dependen casi por completo de este recurso para sostener sus economías. Por ejemplo, el medio millón de mineros del carbón en los estados indios de Jharkhand y Chhattisgarh se enfrenta a un futuro incierto a medida que el país avanza hacia las energías renovables. La provincia de Mpumalanga en Sudáfrica, que genera el 80 % del carbón del país y emplea a casi 90.000 personas en el sector, enfrenta pérdidas de empleo relacionadas con el carbón bajo el Plan de Inversión en la Transición Energética Justa del país. Y los 80.000 mineros de la cuenca de carbón de Silesia, en Polonia, están en riesgo ante el objetivo de la Unión Europea de eliminar por completo el uso del carbón para 2050. Sin estrategias adecuadas de transición, estas comunidades están destinadas a enfrentar altos niveles de desempleo, desintegración social y creciente desigualdad, cuyos impactos resonarán en sus sociedades durante décadas.

A nivel global, las estrategias efectivas de transiciónes energéticas son escasas y, por lo tanto, valen su peso en oro para responsables políticos e investigadores que buscan inspiración e ideas replicables. Aunque no existe un modelo único aplicable en todos los casos —cada transición debe desarrollarse según las condiciones y circunstancias particulares de la comunidad afectada—, la experiencia de Collie, hasta ahora, ofrece lecciones valiosas y transferibles.

El enfoque de Collie es un ejemplo destacado de un proceso de consulta “progresista y dinámico” que prioriza las voces de los trabajadores, según Goods. “No todos los trabajadores están entusiasmados con la transición; algunos son escépticos o ven al carbón como parte del futuro del pueblo. Pero reconocen el valor de la transición para sus hijos y para la comunidad”, observa. A diferencia de muchas regiones que dependen del carbón en el mundo, la transición de Collie se ha caracterizado más por la cooperación que por el conflicto, gracias a la colaboración decidida entre trabajadores, industrias y representantes políticos.

Y tanto en Australia como en otras partes del mundo, muchos ya han comenzado a tomar nota. La nueva Autoridad Económica para las emisiones Cero Neto de Australia (Net Zero Economic Authority, NZEA, por sus siglas en inglés) ha identificado a Collie como una de sus prioridades, reconociendo su potencial como modelo para otras localidades que dependen del carbón y que se encuentran en transición energética. Y según Miffling, el pueblo ha recibido expresiones de interés de lugares como los Emiratos Árabes Unidos, la costa este de Estados Unidos y la provincia canadiense de Saskatchewan. “Tal vez seamos un poco pioneros”, bromea con un guiño cómplice. “Si esto lleva a nuevas industrias, a trabajadores recapacitados y s una comunidad feliz, quizá esa sea la medida definitiva del éxito.”

Collie ha contado con un conjunto de condiciones únicas: una fuerza laboral altamente sindicalizada, vínculos históricos con el Partido Laborista y la propiedad estatal de activos clave como las centrales eléctricas de Muja y Collie. Estas condiciones que facilitan la colaboración entre múltiples actores también existen en países como Alemania y los escandinavos, pero siguen siendo poco comunes en otras partes del mundo. “En lugares como Appalachia, la ausencia de sindicatos organizados y de compromiso político suele generar disidencia e incluso el auge de políticas de extrema derecha”, afirma Ellem.

La fuerza laboral del carbón en Collie está altamente sindicalizada. (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)

Además, el tamaño compacto de Collie y su proximidad a industrias emergentes como el acero verde y las energías renovables representan una ventaja distintiva. Por ello, Goods cree que la posibilidad de replicar este modelo estará limitada solo a ciertos casos. Regiones carboníferas grandes y más dispersas, como Appalachia o la cuenca carbonífera de Polonia, tendrán muchas más dificultades para generar suficientes empleos nuevos e infraestructura. “Incluso en Collie, las oportunidades de transición apenas están comenzando a surgir”, señala Goods. “Llegar a la meta —donde una comunidad cuenta con empleos verdes y seguros— es una tarea increíblemente difícil, y será distinta para cada región.”

Cuando hay un vacío de información, este se llena con especulación, generando incertidumbre.

Aun así, para aquellas regiones que ya están —o están a punto de iniciar— ese camino, pueden extraerse algunas lecciones transferibles de lo que funcionó, y lo que no en el caso de Collie. En primer lugar, conviene subrayar que contar con 662 millones de dólares australianos ayuda bastante. Estas cifras no solo son impresionantes, sino difíciles de encontrar en otros lugares del mundo, lo cual es preocupante, ya que reflejan el nivel de inversión que requieren las transiciones efectivas.

En términos más prácticos, la transparencia ha surgido como una piedra angular de la transición de Collie. “Cuando hay un vacío de información, este se llena con especulación, generando incertidumbre”, afirma Paul Irving, responsable de medio ambiente, comunidad y gobernanza en Griffin Coal. Por ejemplo, aunque en un inicio se temía anunciar las fechas de cierre de las plantas, involucrar a la comunidad de forma directa y honesta ayudó a generar confianza en el proceso.

Paul Irving, gerente de medio ambiente, comunidad y gobernanza en Griffin Coal. (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)

En segundo lugar, los sindicatos descubrieron que enfocar estratégicamente sus esfuerzos de campaña generaba mayores resultados. “Convencimos primero al pueblo, que luego presionó a las empresas para que se sumaran”, recuerda McCartney. Y en el terreno político, los sindicatos apuntaron primero a las figuras clave de la Cámara Alta, cuyo apoyo ejerció presión sobre la Cámara Baja para que también se involucrara. “Solo me arrepiento de no haber empezado a hacer lobbying con el gobierno antes —al mismo tiempo que me acerqué a la comunidad. Estaríamos mucho más avanzados si lo hubiera hecho”, lamenta McCartney.

El tiempo correcto es otro elemento fundamental en una transición. “Existe la idea errónea de que cuando una planta eléctrica cierra, una fábrica verde aparece de la noche a la mañana”, comenta Gunning. “En realidad, hay que enfocarse en activar los terrenos en una secuencia adecuada, para evitar dejar a los trabajadores sin empleo durante meses.” Uno de los gerentes de las plantas eléctricas nos confesó discretamente que está operando con el mínimo de personal, a pesar de que aún faltan varios años para el cierre, ya que los empleados están abandonando progresivamente sus puestos para incorporarse a nuevas industrias.

Darcy Gunning, responsable de campañas del Sindicato de Trabajadores de la Manufactura de Australia. (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)

Por último —y lo más importante—, nada de esto habría sido posible sin reunir a todas las partes interesadas en la misma mesa, a través del Grupo de Trabajo para la Transición Justa, y sin empoderar a la comunidad para que participara en la co-creación del proceso. “La clave fue cercanía con la que el Gobierno trabajó con las comunidades afectadas, tratándolas como líderes del proceso, en lugar de imponer un modelo de ´arriba hacia abajo´”, afirma Hanns. Baggetta ha observado lo mismo en el programa de transición laboral de Synergy: “Hay que planificar y actuar con anticipación, iterar, y priorizar un enfoque centrado en las personas y basado en la co-creación.” El programa de Synergy está guiado por un comité de 40 empleados. “Eso hace que el proceso sea más largo, pero los resultados valen la pena y nadie queda atrás”, señala Baggetta. Y para McCartney, el éxito del Grupo de Trabajo proviene directamente de los principios rectores que establecieron para la transición desde el inicio. “Estos principios funcionan, ya sea en Arabia Saudita o en Tombuctú”, asegura.

La central eléctrica de Bluewaters, cerca de Collie. (Credit: Bill Code)

A medio camino

Pero el orgullo precede a la caída, y en Collie nadie da nada por sentado. El proceso está lejos de haber terminado, y la verdadera prueba llegará cuando la Unidad 8 de Muja cierre finalmente sus puertas en octubre de 2029. “Apenas vamos a la mitad. Aún quedan cinco años por delante”, dice McCartney.

El Grupo de Trabajo para la Transición Justa está concluyendo su primer ciclo de implementación de cinco años, y actualmente está preparando los planes para el siguiente, que comenzará después de las elecciones estatales de 2025. La Unidad de Ejecución de Collie señala que la siguiente fase se centrará en asegurar empleos sostenibles en la industria, expandir el turismo y completar el desmantelamiento de los sitios carboníferos, al tiempo que busca alinearse con los objetivos federales de emisiones netas cero.

También están en marcha planes para atraer a más pequeñas y medianas empresas que respalden las nuevas industrias de Collie, en particular la del acero verde. “Los fabricantes tienden a establecerse cerca de las fundidoras verdes, porque enviar hierro verde por barco anula sus beneficios ambientales”, explica Steve McCartney. Los sindicatos esperan construir una cadena de suministro coordinada en Collie que reduzca la competencia entre empresas, y que al mismo tiempo fomente un mayor uso de herramientas avanzadas, como la robótica. Shaffier, de Magnium, lo detalla: “En cuanto estemos en funcionamiento, podemos dar origen a otras industrias, porque es bastante sencillo tomar el magnesio y, más adelante, montar una empresa de fabricación o aleaciones.”

Una reunión del Grupo de Trabajo para la Transición Justa de Collie. (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)

Asistir a una de las reuniones del Grupo de Trabajo para la Transición Justa en el ayuntamiento de Collie transmite un compromiso con la causa. La sala está llena con representantes de cada sector involucrado en la transición; algunos aún llevan su ropa fluorescente de trabajo, recién salidos de la mina o de la planta eléctrica. Cada quien llega con su propia agenda, pero el ambiente general de las interacciones es de colaboración por encima del conflicto.

El plazo de 2050 para alcanzar las emisiones netas cero se acerca cada vez más, y las posibilidades de mantener el calentamiento global en niveles manejables disminuyen con cada día que pasa. Como el componente más contaminante de nuestro sistema energético, el carbón deberá eliminarse en la mayoría de los países mucho antes del 2050. Y con tan pocos ejemplos de cómo lograr esa transición de forma justa y equitativa, Collie puede celebrarse como un modelo de cómo pueden comenzar esos procesos. El modelo no es perfecto y tiene sus limitaciones, como todos los intentos de transición justa; y, quién sabe, puede que nunca alcance su objetivo. Pero el ideal, de diseñar y construir el cambio social de forma colaborativa, con y para la comunidad , debe considerarse la máxima expresión de justicia en cualquier esfuerzo de transición industrial o económica. La comunidad sabe mejor que nadie lo que necesita para transformar su economía, y cómo empoderarse de forma gradual para que apropiarse del proceso —en lugar de prometer una olla de oro al final del arcoíris— ofrece, por mucho, la mayor probabilidad de éxito para la transición energética hacia las emisiones netas cero.

Para ser un pueblo cuyo futuro pende de un hilo, los habitantes de Collie muestran un sorprendente nivel de optimismo y un encanto sincero y sin pretensiones. Tal vez, en cierta medida, eso refleja la confianza que les ha dado el propio proceso de transición, incluso en esta etapa tan temprana. En Appalachia y el norte de Inglaterra, la ira y la frustración nacen del sentimiento de impotencia y de la falta de agencia y control. Incluso si Collie eventualmente no lo logra del todo, su destino está, más o menos, en sus propias manos. Y eso es lo máximo que cualquiera pueda pedir.

“Si no empoderamos a la gente local cuando intentamos generar un cambio profundo en sus comunidades, entonces estamos en el camino equivocado”, concluye McCartney.

Darcy Gunning, del Sindicato de Trabajadores de la Manufactura de Australia.

Sean Rinder de Premier Coal’s . (Credit: Oliver Gordon / IHRB)